PROCESS FLOW OF A CRIMINAL CASE (PERSPECTIVE OF THE VICTIM)

Gavarni, Paul (n.d. post 1862). Voyages de Gulliver (4th Ed.), Laplace Sanchez et Cie, Paris.

Police as an institution and as individuals are the premier protector of our human rights.

This should be the starting point of your expectations when you or your loved one is a victim of crime. You need some positive energy to get by after what you have been through.

Along the way, you may feel disappointed or lost energy for the case. A criminal case may take a long time to conclude. In the first place, it may have taken a long time for you to report.

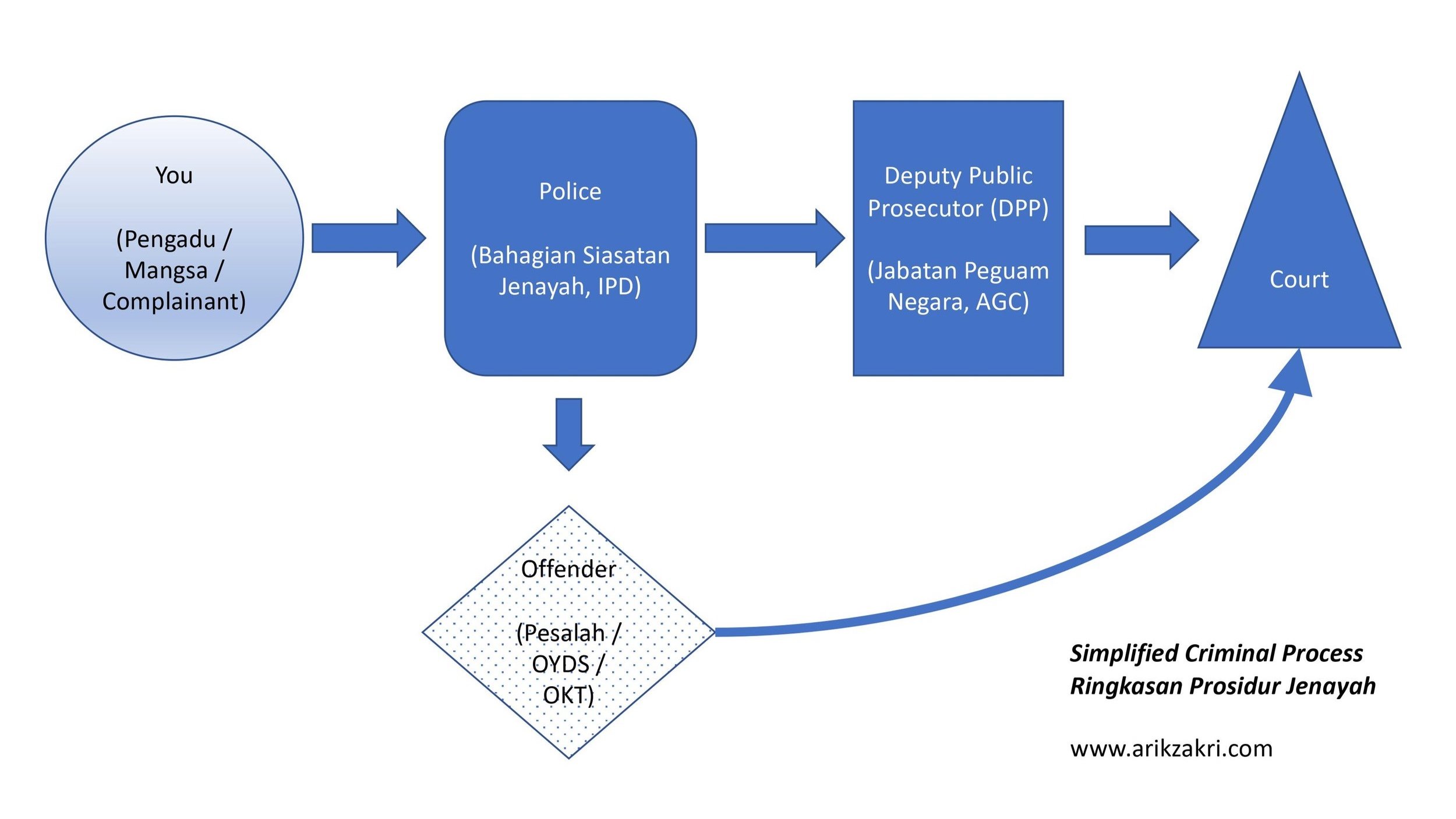

In this writing I am sharing some observations on the process flow for a typical criminal case; this time from your perspective, the victim. Below is a simplified process flow for a criminal case. You begin your journey at the left-most circle, when you make a police report.

Simplified criminal process. The timeline depends on the requirements of the case: collecting and analysis evidence and other factors.

1. A criminal case always begins with information of a criminal offence. A police report is made by a person known as a Complainant (Pengadu). The Complainant may be the victim of a crime, but not necessarily so. Even the perpetrator himself may make the police report – sometimes as a smokescreen or to counteract any accusation against him or for some other reason. A bystander may make a report. An auditor who discovered evidence of fraud in her investigative audit may make a report. Under the law, there is no restriction to who can make a report to the police. I have handled a case where a teenager in Form 2 lodged a police report (and then retracted it a year later) against her school principal. Sometimes the information is given by an anonymous member of the public who dials the emergency hotline 999. The information is relayed to the relevant officer on duty at the relevant police station, who may then make the First Information Report – I have seen it done this way for murder cases where bodies of victims were found by members of the public.

2. You may make a call to the emergency hotline or the nearest Police Station. Depending on the nature of the action taken by the police after that, you may or may not need to make a police report at the Police Station.

3. Theoretically you may make a police report at any Police Station (Balai Polis) nearest and most convenient to you. Gone are the days that police turned complainants away or redirected them to the “correct” police station, purportedly on an imaginary rule that only a police station within the jurisdiction where the crime occurred may receive reports. All police reports are stored in a centralized system that is accessible from any Police Station in the country. Police Stations are open 24 hours a day and you may walk in at any time.

4. A police report may be typed at the keyboard provided at the inquiry counter of the Police Station, or handwritten in a complaint form (as we see in the reports to certain enforcement agencies), or prepared in advanced at home – bring your printout or in thumbdrive. Many Police Stations will ask you to sign 2 copies of the report, which they print behind their counter. You keep one copy. Avoid disseminating or publishing your police report. If you need copies of the said report, you can pay RM2.00 and obtain a certified true copy of the report from the same (or any, I’m not sure) Police Station. The perpetrator does not have the right to see your report until after he is charged – the Deputy Public Prosecutor (DPP) will provide him a copy together with other documents used in support of the charge. If he is charged.

5. You may make a call to the emergency hotline or the nearest Police Station. Depending on the nature of the action taken by the police after that, you may or may not need to make a police report at the Police Station.

6. Sometimes certain persons may discourage you from making the police report or they may use psychological methods to make you withdraw it. They may dissuade you or your witnesses from giving statements to the police. Section 114 of the Criminal Procedure Code clearly prohibits this. In my view it covers statements and reports, even though only statement in the course of a police investigation. The English version remains the official version:

“114. No discouragement from making statement to the police

No police officer or other person shall prevent or discourage any person from making in the course of a police investigation under this Chapter any statement which he may be disposed to make of his own free will.”

For your reference, the Bahasa Melayu version as published by International Law Book Services says this:

“114. Dorongan untuk membuat pernyataan kepada polis ditawarkan

Pegawai polis atau orang-orang lain tidak boleh mencegah atau menawarkan hati mana-mana orang, daripada memberi pernyataan dalam masa penyiasatan di bawah Bab ini yang mana pernyataan itu ia bersetuju dengan kehendaknya sendiri membuatnya.”

7. A good report should be a solid one-pager. Avoid a lengthy report. Your police report should be clear (simple to understand, no dramatic stories), crisp (omit any additional or supporting details; focus on the essential points) and sharp (to the point with emphasis on what is important and discard what is not). Do not get excited. Control your emotions (anxiety, outrage, etc). Your police report may be used in a criminal or a civil court of law. Your report can even be used to impeach you if you are not careful. Someday, you may even wish to “retract” your police report, so make sure that you do not leave any unqualified allegations, unsavoury observations or aspersions that you may regret later. A police report will be in the police system permanently even if you retract it later with a further police report. Only a court order (which I cannot offhand imagine what kind of court order) could obliterate it from history. Do not write pages and pages and pages of drama. Too much detail may not be good for you because if your case goes to trial, it may surface that there were other independent evidence that contradicted or spun your aforesaid assertions against you or against another party in an unexpected manner – by then it is beyond your control and you will need to expend much time and energy at trial putting out the fires of your errors. You need to place just the essential facts to disclose an appearance of an actual case, an offence. You do not need to name all your sources or disclose the number, type and quality of your supporting evidence. All that will be catalogued by the IO during the course of investigation, which could take weeks or months or years to complete. Your lawyer would advise you, that your police report is not an encylopaedia containing the entire facts of the case. It is only the key that triggers the ignition of a combustion engine, setting in motion the machinery of investigation.

8. You should bring these to the Police Station:

a. Your identification documents, unless you lost them or were robbed of them. Even if you are an undocumented person (whether under the protection of UNHCR or any other relevant body), you have the right to make a report and receive protection of the police, however, the moment you make the report, you could expose yourself to some other action.

b. Basic supporting evidence which introduces yourself and your relationship to the case. Do not bring any evidence that affects the crime scene, drugs, firearms, weapons or other items – leave that part to the Investigating Officer (IO) and their forensics team. If your case involves a document, such as your worker’s passport, a purchase agreement, a threatening letter, a photo or map, for example, you may bring those in a file. Make copies for yourself because the IO make take them and you may not see them in a long time.

c. If you are a child, bring a parent or guardian or some adult who can vouch for you.

d. Not a rule of procedure, but it is good to bring some witnesses or other persons who could be helpful to the investigation; someone who you can easily talk to and obtain their cooperation and commitment.

9. You would be referred to the IO on duty. There is a roster that changes every day. The IO would be based at the Police District Headquarters, known as the IPD (Ibupejabat Polis Daerah). Under each IPD are several Police Stations. That IO on duty would be overseeing all new cases from all those Police Stations in that one day. For that reason, sometimes you will need to wait several hours before you are able to meet the IO on duty. A large district may have a dozen or more IOs on duty on one day; a smaller district may have only one single IO in charge of all new cases for that one entire day.

10. For the majority of cases, district IOs are either Sargeants or Inspectors. They could also be Sargeant Major (SM) or Sub-Inspectors (SI) too. For serious cases (e.g. murder), the IO would be Assistant Superintendant of Police (ASP) and above. Do not be confused with administrative terms such as “SIO” (Senior Investigating Officer) or “AIO” (Assistant Investigating Officer, or Penolong Pegawai Penyiasat). As a Complainant, these distinctions should not matter to you. An officer in charge of the investigation of a case is called an IO regardless of rank and remains accountable to the case and to you as Complainant. I have handled a handful of cases where the IO was actually the Head of Criminal Investigations for that particular district; i.e. the boss of all IOs for that district.

11. When you first meet the IO, the most important thing that you must present are as follows. You need not detail them out in your police report.

a. The actual information of the crime. Be clear and simple, no dramatic stories of your fascinating life story please. Make it easy for the authorities to help you.

b. Whether the information provided creates a picture that a crime may have been committed. By extension, the question is whether there was a crime at all.

c. If possible, and if you have strong cause for it, you can name a perpetrator. If you are unable to do so, then you should provide any information on how to identify, recognize and locate them. E.g. social media ID used by them, anyone who accompanied or introduced them to you, their car number plate, facial features such as moustache, whether you met them before. These aforesaid examples were successfully used in cases I have handled in the past; success is not as simple as it sounds though.

d. Any witnesses who can support what you say, or if they cannot directly support, who can still substantiate your complaint. For the purpose of a police investigation (and not necessarily trial), a witness is not only someone who directly saw and heard what happened – it could be someone who is acquainted with the relevant facts of the case. It may be someone who may not be a true “witness” as recognized under the Evidence Act 1950 – it may be a person who knows the whereabouts of a suspect, or who can provide leads to the police to help them discover an item or to locate someone.

e. The injury suffered by you. If it is financial loss, you could attempt to quantify it for the IO. You need not back it up with real valuation or accounting-standard evidence just yet – that can come later. Typically, the IO needs a rough estimation of loss so that they can write it on the outside cover of the Investigation Papers (“IP” or Kertas Siasatan) under the heading of “Nilai Kerugian (RM)”. Don’t worry if it is inexact because at this stage they only need an estimation.

f. Any fear you have now of any current danger or potential harm that the perpetrator may cause upon you. For example, because the perpetrator is stalking you, was caught scratching (“toreh”) your car door, splashed red paint at your house, spread lewd pictures of you, is your immediate neighbor or relative, or has been demanding you pay them extortionate money.

g. You may qualify for a Protection Order under the Domestic Violence Act 1994 (there are 3 types of Protection Orders) if you are currently or formerly married to the perpetrator, or otherwise related to them or could be considered family. There are other types of protective measures that the police can do for you but which are seldom formalized, such as going to the court and procuring that a bond be issued against breach of the peace, and other less commonly-enforced procedures. I presume that because the paperwork is daunting, the police do not resort to these procedures. They just call in the suspects or arrest them.

12. The IO will record your statement, almost always on the same date that you make the police report. If the IO does not do this, you should insist for one; contact their boss at the IPD or consult a lawyer. The IO should receive the supporting evidence from you so keep copies for yourself beforehand. Always reread your statement before signing it. You may request to make correction to your statement before signing it. You are not permitted to keep a copy of your statement, so it is a good idea to note down what you told the police immediately after you leave the session. This is because you could forget what you told them as the months go by. The only time you can see your statement again is if referred for the purposes of refreshing your memory before trial.

13. The IO may interview your witnesses immediately or later. Do not panic if the IO does not record their statements. Just keep in touch with the IO and assure them that your witnesses are willing to give full cooperation as and when necessary.

14. The IO may ask you some pseudo-legal questions that you may not expect an IO to ask. Assume the best, that these questions are backed by professional intentions and years of experience. Perhaps the IO is just testing you. Perhaps the IO is overloaded and needs to prioritise the workload. So keep your cool and refrain from any untoward reaction. Remember, you are the master of your emotions. Be pragmatic because you want the IO to do what you want. Do not give them a reason to eject you from access to your rights due to your own momentary outburst.

a. What is your endgame or objective in making this report? Do you want the suspect arrested and charged, or just to teach them a lesson, to recover something they took from you or owe you?

b. What was the effect of the crime on you? Was it really that serious?

c. Do you really wish to proceed with the case because if the IO arrests the suspect, it will be in their record and will affect their future (and other comments intended to dissuade you from proceeding so that they can close the case).

d. It was your fault, wasn’t it?

e. Why were you so reckless? Why did you dress that way? Why were you knowingly in a dangerous situation?

15. After the your statement is recorded, the IO may proceed to initiate the investigation. An IP shall be registered and the IO will populate it with police reports, witness statements, their Investigation Diary, supporting documents and photos, sketch plans and even the statement of the suspect. Minute sheets containing official communications between the IO, Head of Department, Deputy Public Prosecutor and other relevant officers are also included therein.

16. However, if the crime does not appear to be clear, then your case may just remain as an FTMT (Fail Tindakan Minit Tercerai, if not mistaken, Loose Minute Action File, LMAF) without an IP being registered (but FTMTs do have their own running number). It may require an Order to Investigate (OIT) from the DPP. These are for borderline cases where the criminality of the case does not appear pressing or clear enough. Sometimes, the law itself requires and OIT before proceeding. It is normal for application for OIT to arrive at the DPP’s desk with all the trappings of an actual IP where some preliminary investigations have been carried out, and the OIT is just a formality.

17. Eventually, the IO should locate the perpetrator and record a statement from them. It is not mandatory for the IO to arrest them, even in a seizable case. However, due to the enormous power given to them by the law, and the reality that suspects who are wrongly accused or wrongly arrested seldom sue the police and the government, the IO may just arrest them anyway.

18. Offences are either seizable or non-seizable. Seizable means that the police can arrest the suspect without a warrant. Non-seizable means that the police have to do some paperwork and appear before the Magistrate to request permission to arrest the suspect. This permission comes in the form of a Waran Tangkap. Since the police have the power to classify cases, if they have several options to classify a case, they will tend to classify it as the highest, most serious case. This is so that they will enjoy the privileges and special powers given when they purport to investigate serious cases. The more serious or heavy a case, the more powers the police obtain. Almost all cases referred to me over the years have been seizable cases. The majority of cases that go for trial in the courts are seizable. I hope a criminologist or jurist looks into this someday; it might be a good thing for some court oversight over so important a matter as a person’s liberty.

19. Whether an IP is opened or not, and whether the suspect is arrested or not, there are several possible outcomes:

a. Suspect is charged for an offence. It will not happen immediately; if it does it would be a couple of weeks after investigations have commenced. A clear cut case combined with a motivated IO can get the suspect charged in a short time.

b. Suspect is not charged (yet), but some other action is taken, for example action under the Prevention of Crime Act (POCA), freezing orders under the anti-money laundering laws, referred to the Immigration Department for “tindakan jabatan” i.e. deported, etc. The suspect could be charged later if the law makes it possible. The DPP may instruct further investigations be undertaken by the IO. You really should consult a lawyer to understand what this means for your particular case.

c. NFA (No Further Action). Case is closed.

d. RTM (Referred to Magistrate). Your report did not clearly disclose the existence of a crime having occurred. Something wrong happened, but it is not strong enough or justified enough for the police to go out and arrest someone. When it is RTM, the Magistrate Court is supposed to issue a notice for you to attend court on a particular day for the Magistrate to examine you on what this case is really about. The Magistrate may give directions or certain recommendations accordingly. RTM tends to be cases where the police really want you to not use the police but to resolve it by yourself using your own domestic methods or the civil courts.

Du Maurier, George (1895), wood engraving for Trilby, a novel, Harper & Brothers, New York.

THINGS TO EXPECT IN THE COURSE OF INVESTIGATION (SELECTED CATEGORIES)

1. Domestic violence

Domestic violence flowchart. The most important immediate concern is to separate the victim from the perpetrator. Contact the relevant NGOs or your legal advisor to learn how to benefit from their support at every stage of this process.

a. Police will accompany victim to a medical officer who will examine them for physical injuries. By definition, domestic violence includes non-physical violence such as psychological abuse, but I have seldom seen this work and have witnessed inaction / apathy instead.

b. Refer to Social Welfare Department (JKM or Jabatan Kebajikan Masyarakat)

c. EPO (Emergency Protection Order) and/or IPO (Interim Protection Order) procured by the IO or JKM

d. If a weapon is involved, the IO should recover it.

e. If there were threatening text messages or recordings, the IO would require them.

2. Sexual crimes against children

a. Same as domestic violence above, except that the category of perpetrators include non-family members. There are additional criminal penalties against perpetrators who have been given responsibility of care over such children, such as school teachers, babysitters and nannies.

b. The child victim will be referred to the Suspected Child Abuse and Neglect Team (SCAN) based in certain large hospitals. There are other similar teams such as Child Protection Team (under JKM) and Child Protection Unit (under the police) with similar functions. SCAN is headed by medical officers and sometimes senior paediatric specialists with experience in abuse cases.

c. Once the child victim has been stabilized (I am using my own words), the child victim will be referred to the CIC (Child Interview Centre) probably within the same week. CIC is basically a place where the police can extract evidence of the crime from the child in a secure and accommodating environment. I am aware of CIC which resemble tadikas and daycare centres with walls filled with colourful animals, the floor is littered with toys and mini-slides and see-saws. The IO will guide the child victim to a recording session held in a special recording room, conducted by a special officer. To be court-ready, the recording at the CIC must be for the purpose of trial and recorded as such and not merely for police investigation (the distinction is sometimes disregarded by the authorities, rightly or wrongly). The interview captures on video recording the child victim’s evidence of what happened and what did not happen. If the recording complies with the procedural requirements, then it can be admissible in court against the perpetrator under the Evidence of Child Witness Act 2007.

d. Child victims (and adults too) should undergo follow up therapy and support by organizations and departments who know best.

3. Commercial crime

a. For commercial crime cases (for example, scam cases, cheating, criminal breach of trust, many cases under the purview of the Malaysian Anti-Corruption Commission, Securities Commission and Ministry of Domestic Trade), documents are everything. The IO would therefore require originals of the source documents, boxes and boxes of them. Often the IO will ask you to get them, and sometimes, to bear the cost on your own.

b. The location of the source documents may be located in different places, for example with the banks, with the company secretary, with the share registrar, with the auditor. The IO should obtain them but sometimes they will make you do the leg work. They would “facilitate” by issuing a written order to produce.

c. In forgery cases, the IO would require you to provide several samples of your signatures from existing sources. The IO would also require you to create new signatures by signing many times on a blank piece of paper. Always ask the IO what it is for, and whether you can keep a copy of the latter. Most likely the IO would not allow it. These samples would be referred to a document examiner at Jabatan Kimia or some other relevant institution for purposes of making a scientific comparison with the impugned forged document.

d. The IO may issue or obtain freezing orders against certain accounts if there is evidence of proceeds of crime. Sometimes your friends, allies and innocent third parties will be affected and you may get anxious phonecalls from them on account of your report.

e. Because commercial crimes cases often involve monetary loss (only, usually), it is possible that the perpetrator will contact you and request that you retract your police report in exchange for them paying you off. Consult an actual lawyer about this please. You need to handle this intelligently within the ambit of the law.

f. Bank statements, telecommunication records often take a long time to procure. This can cause the case to protract. Be patient and understanding of this and give space to your IO to do their work. At the same time, do not let go entirely; from time to time you need to follow up with them in writing to remind them you exist. The key concept here is that your follow up should be in writing and not based on trust or goodwill or whether the IO is your new friend.

4. Robbery, extortion, theft, sexual crime with adult victim

a. I’m very sorry, please be prepared with re-traumatising and re-victimisation – you will undergo repeated questioning on the incident again and again and again by the detectives, the IO, sometimes the IO’s boss, the replacement IO, the DPP, the replacement DPPs, the trial DPP, the retrial DPP, the Learned Judge, the Honourable Defence Counsel. I do not wish to demoralize you but this is a weakness of the system that we have been striving to reform for decades. I do not have psychological advice to help brace you, my only tip is you should write down your own notes soon after the incident and remain consistent throughout the investigation as much as possible. Tell the same story even if you have to retell them ten times to ten officers. You do not need to share these personal notes with anyone. Seek advice from a lawyer on referring to contemporaneous personal notes in the witness box, and if it is possible, the pro and cons. Check with the trial DPP because sometimes your notes may contain leads and tidbits that are helpful to them.

b. High and low swabs. Several tests, sometimes nail “swabs”, DNA tests. Google these.

c. Identification Parade (ID Parade or Kawad Cam). You will be summoned to a room with a one-way mirror, overlooking a chamber where a number of persons are standing in a row. This is the ID Parade. A police officer delegated to this task will prepare a report based on your response whether you are able to confirm whether the perpetrator was in this room. Do not feel pressured to confirm whether the perpetrator was in fact in that room. But please do voice your confirmation firmly and clearly if he is. The police may ask you to point out the person you identified, or to touch them on the shoulder. What actually happens varies from IPD to IPD. Identification is a strong, sometimes decisive supporting evidence in robbery and rape cases even in the absence of DNA evidence. In my view the system should be reformed to reduce victim’s exposure to perpetrators in the ID Parade and for the law to require a photograph of the actual ID Parade in session to assist the court to consider whether the composition of the members of the ID Parade was fair. I am not sure, but I think if you sense something wrong with the ID Parade, e.g. if to you it looks ridiculous, please contact the IO and ask him if he can fix the absurdity you detected. If you are asked to sign any forms (e.g. forms related to the ID Parade), only sign off when you are satisfied on the correctness of the document. Do not allow yourself to be a rubber stamp for the officer conducting the session, whose objectives, KPI, motivations may differ from the IO and from yours.

d. You may be shown items recovered from the perpetrator or from pawn shops that he had fenced them to – you need to identify whether any of them were stolen from you. Even if you were murdered, your close relatives and friends should be able to identify your personal belongings. Such evidence was instrumental in a number of murder cases I prosecuted.

e. You may be brought to the crime scene. Ideally the crime scene is not tampered so that the police have access to fresh evidence where they may recover swabs from pillows, bedsheets, toothbrushes, unwashed undergarments, fingerprints on windowpanes, car steering wheels and phone screens.

5. Cases Related to Consumer Rights and Illegal Hunting / Poaching of Protected Animal Species

a. There could be a test purchase or raid conducted by Ministry officers on the suspected business or premises who are breaking the law, price fixing, hoarding, smuggling or poaching.

b. The enforcement agency has the power to seize and destroy large inventory under the relevant law.

c. Certain laws authorize payment of a reward to informants such as yourself.

6. Environmental Protection cases

a. For polluted river cases, the relevant agency would conduct sampling and testing of several river bodies and waterways to establish the origin of the contamination.

b. Though not essential for the case, for the purpose of sentencing and perhaps even bail, if you could produce medical reports or other expert input on the effects of the contaminants on yourself and people in the community, it could help the enforcement agency persuade the Court to make the necessary orders to prevent further harm and to effect a weighty penalty that is not merely a business cost to the responsible party.

ARREST AND REMAND (TANGKAPAN DAN TAHANAN REMAN)

You will not be involved in this process but the IO may notify you when it happens. During the course of remand, you may be contacted by the family of the perpetrator who seek your cooperation to help procure his release. Be cautious if the person contacting you is a lawyer, tout/middleman, or a police officer unrelated to the IO. Just cross check with the the IO but be wary if an IO is in cahoots with negative elements. If you have evidence that the suspect has tampered with evidence or will likely interfere with you or your witnesses, please inform the IO and request they inform the Magistrate to factor into remand period. Remand should not be punitive but if the perpetrator is out, the case can be sabotaged due to his self-preservation efforts.

The police have the power to release a suspect at any time during arrest, even before the expiry of a remand period. They should release him on police bail. The IO is not obliged to update you when the suspect has been released, so keep your eye on the ball.

CHARGE (PERTUDUHAN)

No one can stop you from attending the charge (unless the offender is a minor or involved in a security offence). But I believe you do not want to attend. I would not advise you to. Consult a lawyer if you really want to see the perpetrator hauled to court. Please do not publicise the case; speak to a lawyer— do this properly if you really think you need to. Because there are rules concerning publicity of ongoing cases.

Depending on the type of charge, the perpetrator (now called an Accused or OKT, Orang Kena Tuduh) may be released on bail by the Court after he is charged. The Court shall fix conditions to bail, for example an amount of money paid to court as a deposit, one or two guarantors called bailors, surrendering his passport, and others. It is normal for the Court to include a rather generic condition that the Accused is prohibited from physically coming near you. Such generic conditions tend to be vague and easy circumvented with some ingenuity. Please contact the IO or speak directly to the DPP in court if you are concerned that the Accused may harass you or your witnesses; be prepared with proof. You do not have the right to speak to the DPP in court, but you can try to give it a shot. Dress well and be polite and unimposing, yet assertive so that the court police guards do not brush you aside. Inform the DPP:

If you or your family is genuinely in fear of the OKT and his henchmen that he will continue to stalk you and harass you.

If the OKT knows where you live, your phone number, works at your workplace, and is likely to call and intimidate you. You need proof of this not mere allegations

If you recently received threats even while the OKT was in detention, and you can prove the threats were linked to the OKT or his relatives/ henchmen. You should have informed the IO earlier, though.

If the OKT is a repeat offender against you, or if you know he is a repeat offender and member of some gangs. You need evidence of this, but let the DPP do as he sees fit.

With such information (and ideally, evidence), the DPP will have basis to object to bail outright (for non-bailable cases), or at least request for high bail or strict terms. I have observed that Protection Orders under the Domestic Violence Act 1994 are issued by some Magistrates almost automatically for domestic violence cases. But in some courts, the Magistrate does not issue a Protection Order automatically, including in one matter that I am presently handling. The effect of not issuing a Protection Order at the time of the charging is that the victim must go to the IO, JKM or themselves apply to court for a Protection Order. So ask the DPP to request for a Protection Order from the Magistrate, on the spot.

Do not treat the DPP like your private lawyer. They do not owe you anything and represent the State, not you. They are not obliged to pick up the phone if you call them, or to respond to e-mails or text messages.

Férat, Jules (n.d. but fl. 1829-1906), L'île mystérieuse by Jules Verne.

TRIAL (BICARA)

Seek professional advice on the expected length and requirements of trial. It depends on many factors such as the number and type of charges, the number and type of witnesses, the availability of evidence, the schedule of the court, prosecutor, defence counsel and even the IO, and other factors beyond your control.

A good prosecutor would instruct the IO to arrange for you to attend a session before trial to prepare. You will be asked to refresh your memory with your witness statement to and perhaps to answer a few questions directly from the DPP in the presence of the IO.

You should keep abreast of the development of the trial and do not surrender it completely to the Court or the Prosecution or the police. If you do not monitor the case yourself, you may be jolted into a trial without being prepared and informed on short notice and at a time that is inconvenient to you. In such scenario, could you expect the quality of your evidence to be unaffected?

When you maintain good communication and rapport with the IO and the trial prosecutor (bonus points if you are in touch with the court interpreter and the police guard stationed in the court room, who takes care of the subpoena lists), you will be better prepared to go to court. Also, you will detect signs of plea bargaining taking place, representasi issued or other things that some people may not want you to know about (because they know you can make an issue out of it). You may not want a case to be withdrawn suddenly, or quietly disappear or DNAA, or perhaps an allegation from the IO that you are uncontactable. When you detect these things, you can intervene in a more timely manner, and not after the Accused has been discharged.

I repeat, do not treat the Prosecutor as your private lawyer and do not abuse them or stress them out. They represent the State and handle tens of cases every week (every day at Magistrate court level). As reminded above, be patient because in this process, you will need to retell your story again and again and again. I remember in my first criminal breach of trust trial, the complainant a company director informed me wearily that I was the fourth prosecutor she was telling her story to, because the prosecutors kept changing one after another as the months passed, without the trial taking off.

For continuity, if you have the need to write to the prosecutor’s office, write to the Pengarah Pendakwaan Negeri for state-based cases and the Ketua Bahagian Pendakwaan for cases overseen by AG’s Chambers in their Putrajaya headquarters. If the prosecuting agency is undertaken by the Securities Commission, MACC or other organization, their designations may differ so please check on them.

On the date of trial, you would be asked to appear at the court and date and time as printed on the subpoena, which you should receive from the IO. If you do not receive the subpoena, please ask for it. Sometimes new subpoenas are issued if the case is postponed. Sometimes, new subpoenas are not issued but instead, the new dates are endorsed on your copy of the subpoena (“kaki sapina”). There are procedures for you to claim compensation for travel to the court. Please check with the court staff on this matter – I suspect you need to produce the actual subpoena because the Court would endorse it (chop and write the date in pen) every time you attend Court. Even if the case is adjourned, you need to seek out the court staff and ensure they endorse your subpoena as evidence that you attended. All these subpoena procedures above differ slightly from district to district and what actually works for your district may not reflect what I wrote above.

I know of at least one agency that often calls up witnesses to court by mere phone call from the IO (or his assistant, or even some other staff from his office) the evening before trial. So these unsubpoena’d witnesses attend out of fear (and perhaps to avoid being charged themselves). Some police witnesses attend on the basis of “semboyan”, basically memos sent by fax. Sometimes DPPs do not even realise that the subpoenas they applied for were not even picked up nor served by their decorated IOs. But this observation has been witnessed for a small number of IOs and does not apply to the majority of our dedicated investigation staff.

After the date of charge, you may sense that the IO is less committed to the case and shows less energy than during the early days leading up to the charge. I think this applies to the majority of IOs across all agencies except but for a few. This is because after your case has been charged, they must focus their attention to new cases or return their attention to old cases that competed for their attention before you arrived. That being said, there are many dedicated and passionate IOs out there who remain close to the complainant and maintain the empathy and rapport. Some IOs are just like that, some are motivated, some are inspired by the energy of the DPP.

For that reason, the best person that can link you with the Court is actually the DPP. The DPP knows exactly what is happening to the case at court, more so than the IO. As mentioned, DPPs do not owe you any service, therefore you or your company should consider appointing a lawyer to follow the case at court and to report its developments to you. This could be especially helpful whether or not you are presently or contemplating launching a civil claim against the perpetrator.

You will be placed in a witness room (bilik saksi) before you are called to testify. In places like Mahkamah Selayang and a number of courts in Shah Alam Court Complex, for example, there is no proper witness room, therefore you will sit on benches outside the entrance to the court room. Sometimes, you will wait there for hours unattended. Sometimes, you have to sit next to witnesses or even relatives of the perpetrator. If I remember correctly, the witness room at cozy Putrajaya Court has thick carpeting and tantalising air-conditioning that can lull you to sleep. Kuala Lumpur Court Complex has well-designed witness rooms with side entrances separate from the main walkway (though a bit claustrophobic without windows). Speak to the IO about such waiting arrangements. Your case may be postponed uneventfully many times and you would need to attend court many times over several months.

If you maintain good communication with the IO (or better, the DPP), you can try to make sure that they call you to court only when you are needed to testify. For sexual cases and robbery cases for example, often the complainant is the first or second witness called. So you can expect to be called early in the trial. All the more reason for you to keep tabs on its progress because you would not be “involved” in the case for a long time. Please note that under exceptional (uncommon) circumstances, you may be recalled to testify, with permission from the court, on application of the Prosecution or the Defence. Please check with the DPP if you are interested to sit in and spectate the testimony of other witnesses. The Court may or may not allow it. It should not be an issue if your relatives or lawyer spectate, though.

When it is you turn to testify, you will be called into the court room. Sometimes it is cold so you should wear heavier clothes, or humid and stuffy, so you should dress appropriately. And speaking of dress, wear clothes that are dignified and proper. No killer colours please. Always have a bottle of water to hydrate. I will not deal here on the subject of your actual testimony, the questioning by the prosecutor and the defence counsel, and the general etiquette.

After your testimony, and the testimony of other witnesses for the prosecution, the court will fix a date for submission at the end of the prosecution case, often lead by the DPP. It used to be called just “submission of no case to answer” lead by the defence counsel instead. This is not very interesting so you need not attend. You may want to attend the date that the Court announces its decision whether a prima facie case has been proved and whether the Accused will be called to enter his defence. This is because, many Courts will straight away order the Accused to testify straight away on the same day. Some will give another date to do so.

Check with the DPP whether they need you around when the Accused is testifying; not to spectate but as a reserve rebuttal witness. Nothing buries an Accused’s testimony like a solid rebuttal with affirmative, independent evidence and supported by this and that. Do not be upset with your prosecutor if you are not called as rebuttal witness : sometimes enough damage is done to the Accused from his own words, that it is best to leave his boat alone to sink with his case.

At the end of the Defence case, the Court will fix a date to hear submissions at end of the defence case and the Court may decide on the spot or on another date. This decision is whether the Court finds him guilty or not guilty.

If the Court finds the Accused guilty, it will then decide on the sentence to be imposed based on the range of punishment permitted by law for that particular offence. The Court will invite Defence Counsel for mitigating factors. A lot of court-resident DPPs normally just stand up and say, “Mohon hukuman setimpal” and sit down. DPPs and prosecuting officers from agencies invariably ask for heavy sentences to push the strong message of their departments to the public.

As a Complainant and victim, you have the right to make a Victim Impact Statement (“VIS”). The VIS is given at the stage of sentencing and shall be considered by the Court when formulating the appropriate sentence against the Accused. Without a VIS, the Court can still impose a sentence because the DPP may have other material to submit for an aggravated sentence. However, in my view nothing strikes the heart more than the personal anguish from the actual victims who suffered from the acts of the Accused.

The VIS may be presented by the DPP just handing in a written statement from the Court. Most effective is if you personally attend and testify. Support your VIS with medical reports and other material to show the full impact of the crime, including financial loss. Include costs for physiotherapy, costs for psychological rehabilitation, renovating or renovating your home or office, any quantifiable loss to your business including the loss or cancellation of confirmed contracts (i.e. confirmed jobs that were cancelled because of the incident, maybe the crime spooked your former partners and customers). Do not assume that the DPP exhibited all that needed to be exhibited in trial, because they are focused on establishing the ingredients of the charge and not proving the impact of the crime on your life. Speak in a dignified and honourable tone, speak directly to the Court, as though saying that “this is the time I am asking for justice now”. Make it count and strike it true to the Judge’s heart and mind. Of course, do not embellish and speak the truth. The Defence Counsel may occasionally object or challenge your VIS, but let them deal with it. At that stage, the lawyer is just fighting hard to save years of prison from his client – the fact of prison is a done deal if prison is the likely form of punishment.

Put in a word that you ask for compensation to be paid to you. Under Section 426 of the Criminal Procedure Code, it is the DPP who makes the application. But give it a shot. Speak to the DPP beforehand to get their support. It helps if you could substantiate your claim with, as mentioned above, medical reports, and other documentary evidence.

Rarely is a Newton hearing conducted by the Court to determine dispute on issues of sentencing. I learned about this interesting procedure from my former head of department who pointed me to two authorities decided by His Lordship Vincent Ng. As Complainant, don’t worry too much about this. His Lordship Asmadi Hussin JC did opine in Mahkamah Tinggi Malaya di Taiping, Rayuan Jenayah No: AB-41H-16-10/2017 Pendakwa Raya lawan Khamallul Khisham Saiful Ismail that:

“Kegagalan Puan Majistret membuat Newton hearing merupakan suatu salah arahan melalui tiada arahdiri”.

In my view, if the Court is conducting a sentencing hearing, your VIS is only one part of the entire continuum of the sentencing process. Thus it should not stop the DPP from calling new witness (or re-calling earlier witnesses, but only on point of sentencing) in support of your VIS. But that is just my opinion.

Whatever is fair for you should be fair for the Accused. The Defence should also be given the right to challenge and rebut your VIS.

It could be that a brief yet wistful VIS is more effective than a lengthy one loaded with documents. The Court would decide based on evidence before it, to such extent that the VIS and Newton hearing can be considered “evidence” as normatively understood. In my personal opinion, this is where personal sentiment counts the most.

AFTER THE CASE : APPEAL

Any party dissatisfied with the decision of the trial Court may file a Notice of Appeal against the entire or part of the decision. Party here means the Public Prosecutor or the Accused and does not include you. If you are dissatisfied with the trial outcome, you may write to the DPP to implore them to consider appealing. They have 14 days to file and appeal (or a cross appeal to enhance sentence, if the Accused is appealing). It is ultimately their decision to appeal or not to.

You should check in whether an appeal has been filed in time. If the time has passed and you are informed that the DPP does not intend to appeal, you may consider writing to the High Court to review the matter under its power of Revision, which may be initiated on its own motion without relying on either party (but, properly, to invite parties to appear to assist the Court and to be present in case a decision is made against them on revision). This is only possible for cases originating from the Magistrate or Sessions Court. If the case originated at the High Court (murder, certain forms of kidnapping and firearms offences, for example), there is no similar avenue recognized because the Revision jurisdiction in the context I mention relies on judicial power which is codified under the relevant law, and available to the High Court only. The Court of Appeal and the Federal Court do not have this power in this manner (but I accept they do have reserve and inherent and paternal supervisory jurisdiction in their respective spheres). Whatever the decision of the High Court (to accept your request or not to), you do not have the right to know the outcome of such request. In fact, the High Court can decide a case on revision without calling any of the parties.

There is another method which is to file a Notice of Motion (Notis Usul) but I do not know how that can be done by a third party such as a Complainant. Do not confuse third party in this context with third party in anti-money laundering proceedings.

AFTER THE CASE : OTHER CIVIL ACTIONS

This is beyond the scope of this writing. However please know that the civil procedure puts the Complainant in the driver’s seat in control of the institution and direction of the case, unlike the aforesaid criminal procedure, which although much cheaper than civil, is lead by the DPP and police. And rightly so because a criminal case is not owned by you but it is property of the State. Civil procedure addresses a different set of concerns and thus provides a much wider set of remedies to benefit you and secure your interest.

HELP IS AVAILABLE

Apart from the police, the courts and lawyers, various bodies provide support services, though sometimes the services are quite situational and may not address your specific needs in every situation. I have referenced some contact details on the first page of this website.

Non-Governmental Organisations provide various support services, including temporary protection shelters, victim support, crisis management and others. Women’s Centre for Change (Penang), Women’s Aid Organisation and other NGOs help protect and assist people who face domestic violence and other abuses.

Social Welfare Department (Jabatan Kebajikan Masyarakat) have branches in every district and provide a range of services to families facing crisis. JKM officers also have the power to issue Emergency Protection Order and undertake protective custody of children from dangerous homes and situations.

Legal organisations such as the Legal Aid Centres provide legal advice and assistance to the poor. Myself and my colleagues have organised Free Legal Aid Clinics every year since 2015, having served around 50 individual cases for the poor.

CONCLUSION

It is hard enough for victims of crime to come forward to make police reports. There are social, economic and other barriers to doing so. They take risks and make sacrifices, lose friends and get stigmatized for doing so. The State does them no favours either, but it is the only entity that controls law enforcement. The least you can do as a Complainant is to educate yourself with your rights and be aware of what is going on with the case. Criminals can be resourceful and desperate and will find ways to escape being punished by the law. One weak point that can be exploited is a complainant who is ignorant or apathetic, out of touch with the case and unlikely to complain to the IO’s boss or DPP’s boss or the Court.

The easiest ticket to their freedom (i.e. the criminals) is not weak laws or weak politicians but it is Complainants who trust the system “too much”. Complainants should not let go but remain vigilant. It is exhausting and tiresome, but it is the only way that a Complainant (and sometimes the DPP or even the Court) prevent the collapse of criminal prosecution (DNAA, postponements, unnecessary acquittals, unprepared witnesses, ungathered evidence, etc).

I wish to conclude this with one last point. Sometimes the Complainant may not want nor need the perpetrator to be fully prosecuted and jailed for years on end. Sometimes, the Complainant just needs immediate relief from harassment or threat from them. If this is what you need, then make that report but be up front with the IO. This takes some savvy so that the IO does not deprioritize or worse, refer your matter to the (figurative) rubbish bin. You can “retract” your report later but there are pro and cons; being up front too early may thus give the police an underestimation of the seriousness of your case and this may endanger you and your loved ones. Whatever your course of action, the only worldly power you can rely on is your own knowledge, so educate yourself.